A properly made reed, in tandem with a good mouthpiece, well-serviced instrument, and fundamentally sound embouchure and air support, is essential for producing a good, characteristic clarinet sound.

The old saying “you get what you pay for” is very true in the reed market. Most reed companies produce reeds that do not go through a strict quality control regimen. As a result, inconsistencies are common in a box of reeds. Ask most professional clarinetists and they will tell you that they routinely get 3-5 good reeds out of a box of 10. The reason lies in harvested cane. Cane (Arundo donax, of the grass family) is subject to any abnormal growing condition. Too much moisture in a season will cause xylems to be too large; too little moisture will cause them to be too small, etc. Heat, disease, and insect infestation are all variables that contribute to a particular harvest being inconsistent. Most reed manufacturing companies purchase cane on the open market. Part of the reason for their inconsistency is also that they make all of their purchased cane into reeds, regardless of any imperfection from the elements in the cane. *As I recommend for the purchase of any product, test every brand of reed that you can before determining which one to use. Always be open to new products, as products made by reputable companies should be improving over time.

A colleague has developed a new strain of Arundo donax, called Arundo donax Musicalis, which has been hybridized to be more consistent in its growth habits. This is exciting for the woodwind community. Possibly, better cane will be available for reed making companies, which will only serve to give clarinetists better reeds. Hopefully, Arundo Donax Musicalis will be a success after it has gone through rigorous testing.

What to Look for When Examining Reeds

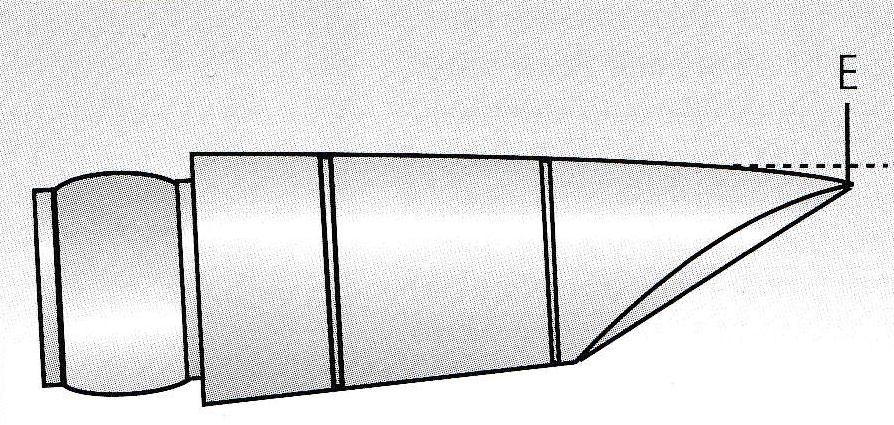

Holding a reed up to a light source should reveal even, fairly close lines (xylems) that run vertically from the butt of the reed to the tip. The cane should be yellowish/white in color, not greenish. Looking at the center of the cut area of the reed should reveal a dense section of wood, called the heart. The tip should be rounded and in the shape of the mouthpiece tip. The ears should look evenly thick on both sides.

How to Choose the Right Reed Strength

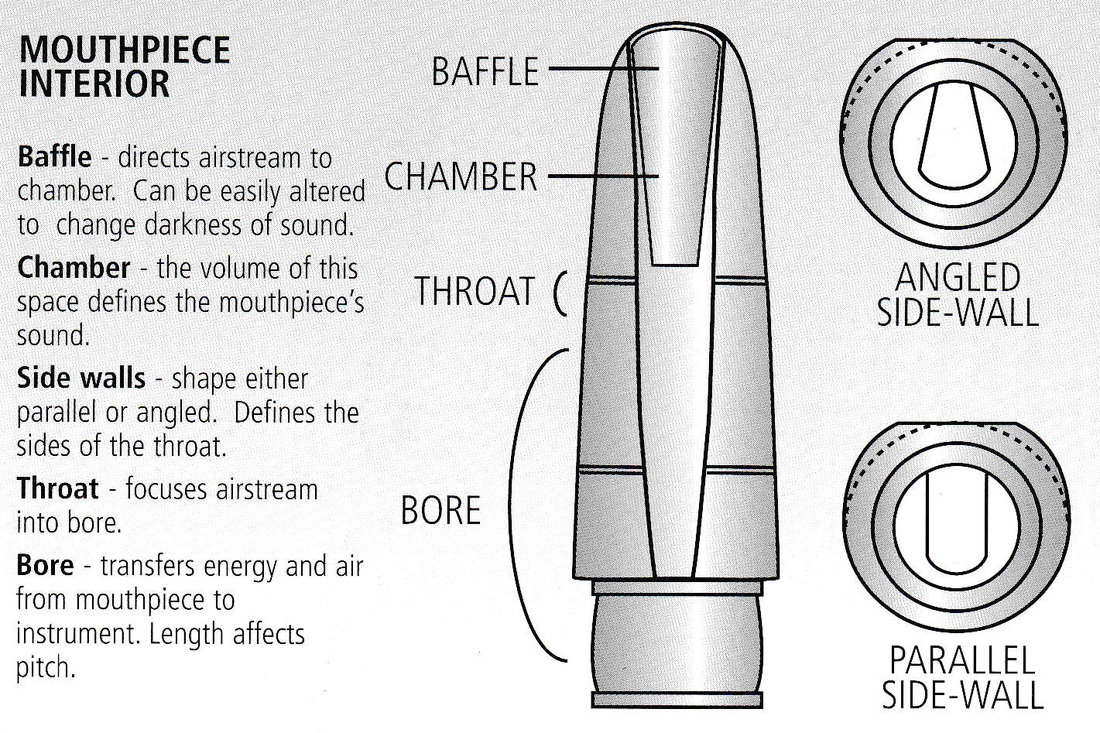

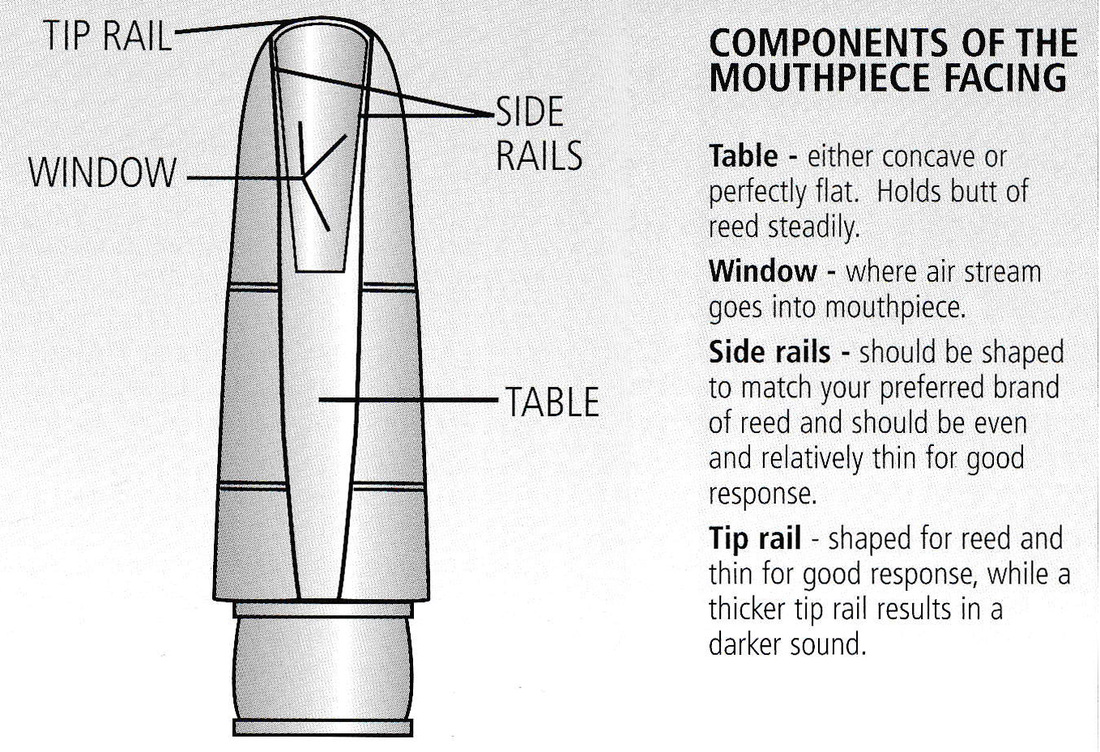

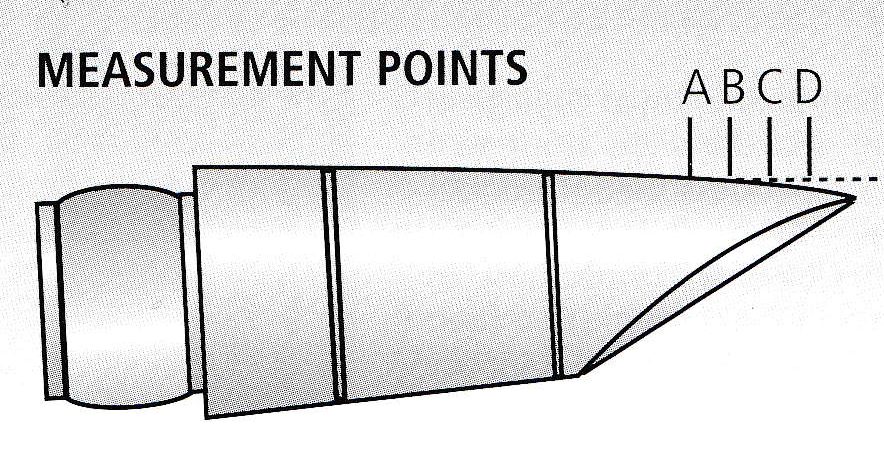

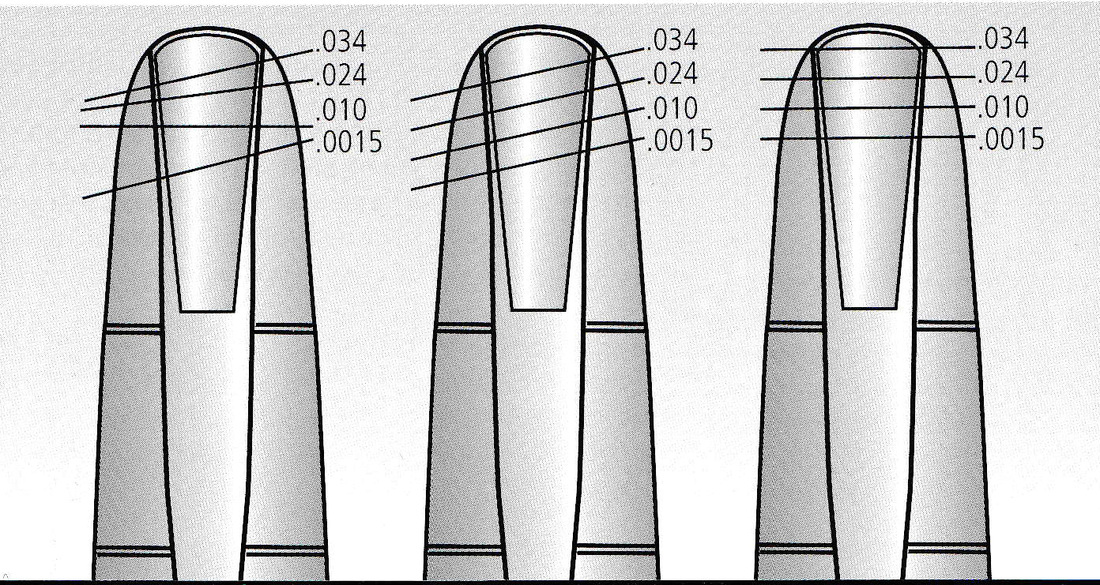

A mouthpiece’s facing and tip opening determine the strength of reed that is required for the best sound. A wide-open mouthpiece requires a soft reed; a close mouthpiece requires a hard reed. A mouthpiece manufacturer should have recommendations for reed strengths associated with each model of their mouthpieces. For students, I recommend a medium close facing, which should be used with a 3, 3.25, 3.5, 3.75 or 4 strength reed. This combination will provide resistance to the beginning student and will be a little difficult to play, but once a proper embouchure is learned, facial muscles are developed, and use of proper airstream support, the student will produce a good, characteristic clarinet sound quickly. I recommend purchasing several reed strengths in the range of what is suggested and test them all, preferably with a clarinetist or teacher listening.

How to Make a Good Reed Better

After finding the right brand and strength of reed for you, you can make even the best commercially produced reed better. The main problem with reeds on the market today, except for the inferior cane problem, is that the reed manufacturing process makes it almost impossible to produce a perfectly balanced reed. Variables of cane denseness and rigidity even within one reed can make one side of the reed vibrate differently from the other side. For a reed to work efficiently (avoiding too much resistance, squeaking, chirping and dull sound), both sides must vibrate equally. To test this, I employ a technique I call the “side to side test”.

Put the clarinet in your mouth as if you are going to play normally. Then, twist the entire clarinet counter-clockwise in the mouth and blow (it is helpful to also tongue rapidly for this test). You are testing the right side of the reed. Next, twist the mouthpiece clockwise to test the left side of the reed. If one side or the other is lower in pitch and harder to blow and tongue, then that side is unbalanced on the heavy side—either thicker, or denser. To correct this, remove the reed from the mouthpiece and remove some material with either a sharp, non-serrated knife, sand paper, reed rush, or other tool. [As a professional clarinetist, I use a tool which makes balancing reeds easy and accurate every time. The Reed Wizard, invented by Ben Armato, former clarinetist with the New York Metropolitan Opera Orchestra, makes reed adjustment very simple. You place a reed on his machine, and then scrape it with the metal blade, and the reed comes out of the machine ready to play.]

The old saying “you get what you pay for” is very true in the reed market. Most reed companies produce reeds that do not go through a strict quality control regimen. As a result, inconsistencies are common in a box of reeds. Ask most professional clarinetists and they will tell you that they routinely get 3-5 good reeds out of a box of 10. The reason lies in harvested cane. Cane (Arundo donax, of the grass family) is subject to any abnormal growing condition. Too much moisture in a season will cause xylems to be too large; too little moisture will cause them to be too small, etc. Heat, disease, and insect infestation are all variables that contribute to a particular harvest being inconsistent. Most reed manufacturing companies purchase cane on the open market. Part of the reason for their inconsistency is also that they make all of their purchased cane into reeds, regardless of any imperfection from the elements in the cane. *As I recommend for the purchase of any product, test every brand of reed that you can before determining which one to use. Always be open to new products, as products made by reputable companies should be improving over time.

A colleague has developed a new strain of Arundo donax, called Arundo donax Musicalis, which has been hybridized to be more consistent in its growth habits. This is exciting for the woodwind community. Possibly, better cane will be available for reed making companies, which will only serve to give clarinetists better reeds. Hopefully, Arundo Donax Musicalis will be a success after it has gone through rigorous testing.

What to Look for When Examining Reeds

Holding a reed up to a light source should reveal even, fairly close lines (xylems) that run vertically from the butt of the reed to the tip. The cane should be yellowish/white in color, not greenish. Looking at the center of the cut area of the reed should reveal a dense section of wood, called the heart. The tip should be rounded and in the shape of the mouthpiece tip. The ears should look evenly thick on both sides.

How to Choose the Right Reed Strength

A mouthpiece’s facing and tip opening determine the strength of reed that is required for the best sound. A wide-open mouthpiece requires a soft reed; a close mouthpiece requires a hard reed. A mouthpiece manufacturer should have recommendations for reed strengths associated with each model of their mouthpieces. For students, I recommend a medium close facing, which should be used with a 3, 3.25, 3.5, 3.75 or 4 strength reed. This combination will provide resistance to the beginning student and will be a little difficult to play, but once a proper embouchure is learned, facial muscles are developed, and use of proper airstream support, the student will produce a good, characteristic clarinet sound quickly. I recommend purchasing several reed strengths in the range of what is suggested and test them all, preferably with a clarinetist or teacher listening.

How to Make a Good Reed Better

After finding the right brand and strength of reed for you, you can make even the best commercially produced reed better. The main problem with reeds on the market today, except for the inferior cane problem, is that the reed manufacturing process makes it almost impossible to produce a perfectly balanced reed. Variables of cane denseness and rigidity even within one reed can make one side of the reed vibrate differently from the other side. For a reed to work efficiently (avoiding too much resistance, squeaking, chirping and dull sound), both sides must vibrate equally. To test this, I employ a technique I call the “side to side test”.

Put the clarinet in your mouth as if you are going to play normally. Then, twist the entire clarinet counter-clockwise in the mouth and blow (it is helpful to also tongue rapidly for this test). You are testing the right side of the reed. Next, twist the mouthpiece clockwise to test the left side of the reed. If one side or the other is lower in pitch and harder to blow and tongue, then that side is unbalanced on the heavy side—either thicker, or denser. To correct this, remove the reed from the mouthpiece and remove some material with either a sharp, non-serrated knife, sand paper, reed rush, or other tool. [As a professional clarinetist, I use a tool which makes balancing reeds easy and accurate every time. The Reed Wizard, invented by Ben Armato, former clarinetist with the New York Metropolitan Opera Orchestra, makes reed adjustment very simple. You place a reed on his machine, and then scrape it with the metal blade, and the reed comes out of the machine ready to play.]

Using the Reed Wizard and the next step are the only things I do to reeds to make them play well. After you have played a reed for a day or two, the flat part of the reed tends to warp slightly. It is necessary to flatten this with very fine (400-1200 grit) sandpaper on a piece of glass (a plate of glass provides a perfectly flat surface). If a reed is playing sluggishly, it is amazing how much better it will play when the back is flattened. It is necessary to “refinish” your reeds on a regular basis. When saliva enters the xylems of the reed, warpage continues to occur, so you may find yourself flattening the table and balancing the reed several times over the course of a reed’s life.

One of the biggest problems with young clarinetists is that they play with poorly manufactured and finished reeds. The warping described above also contributes to a reed responding inefficiently. Constant attention and periodic adjustment to the balance of a reed is necessary to prolong the life of a reed and to keep it playing as well as it can. It is amazing how much better a reed will play and your clarinet section will sound if each student is playing a good reed that is properly balanced.

One of the biggest problems with young clarinetists is that they play with poorly manufactured and finished reeds. The warping described above also contributes to a reed responding inefficiently. Constant attention and periodic adjustment to the balance of a reed is necessary to prolong the life of a reed and to keep it playing as well as it can. It is amazing how much better a reed will play and your clarinet section will sound if each student is playing a good reed that is properly balanced.

*As a professional clarinetist, I have found a brand of reeds that provides me with 100% playability in a box. I have visited the Canyes Xilema reed factory in Valencia, Spain on several occasions. The owner of the company, Inma Herrera, explained to me that when she goes to cane auctions in the Mediterranean region, every large company is there, bidding on cane. So, every reed company is using the same cane, contrary to what you may have heard. In Inma’s case, she throws away 40-60% of the cane that she purchases, because it is inferior. My theory as to why other companies have 30-50% playability in a box, is that they are not throwing away inferior cane. Additionally, she monitors the mechanical adjustment of her machines on a regular basis, and employs professional clarinetists to test her production, resulting in the most consistent reeds I have tested on the market.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed